Oakwood, Ohio is a classic first-tier suburban city. So at first glance the home at 413 Wiltshire Boulevard might not see distinctive. It is a classic example of an Arts & Crafts or Craftsman bungalow. What you cannot see is that the house has had no additions and essentially no alterations. And because of that, the Oakwood Historical Society is inviting you to take a tour back in time.

Mr. Freud, a local businessman, built the house in 1929 in the midst of Oakwood's construction boom. Interestingly, Mr. Freud previously built the house next door at 407 Wiltshire in 1926. Why he built two houses next door to one another is not known. We do know that Mr. Freud was a grocer. He owned Freud's Grocery, later called Freud's Pure Food Markets, in Dayton. His first store was at 773 Huffman Avenue. He later expanded to three locations when he established shops at 907 Salem Avenue and 1941 E 3rd Street. Charles and his wife Anna had no children and were 39 and 43 years old when they moved into Oakwood in 1926.

The Freud's house at 413 Wiltshire is an example of an Arts and Crafts bungalow. The Arts and Crafts style was one of the most popular architectural styles of the early twentieth century. Bungalows, which were often in the Arts and Crafts style, were the most popular house type of the 1920s. Bungalows represented suburbia and were the perfect home for a city like Oakwood with its large lots (when compared to Victorian city lots -- like what you would see in the Oregon District). The bungalow was also very modern with its open floorplan and built-in bookcases, benches, kitchen nooks, and cabinets. Unlike Victorian neighborhoods, a city like Oakwood was built with city sewers and all the houses had indoor plumbing and were designed with indoor bathrooms, something we take for granted today. Another unusual thing about 413 Wiltshire is the attached garage. It was typical for houses built in the 1920s to have a detached garage because not every household owned a car and the streetcar was the way most people traveled. Secondly, because automobiles were still new and not well understood, many people believed that cars might catch on fire. If the garage was attached to the house and caught on fire, it would result in a house fire. As a result, it was common in the 1920s and '30s to build the garages separate from the house; it was not until the 1940s that most new homes were built with attached garages.

The Freuds remained in Oakwood until 1932, when they sold 413 Wiltshire to J. Clifford Hull and his wife, Katharine. The Hulls moved from a house at the corner of Salem and Holt avenues to Oakwood. J. Clifford was 59 years old and a retired assembler from a foundry. Katharine was 52 years old, and the couple had no children.

The Hulls lived at 413 Wiltshire until 1940, when Harry Costas and his family moved into the home. The Costas family remained in the home for 72 years. Living in a home in Oakwood for 72 years is not unheard of. However, the owners of this house were unusually neat and organized, and also savers. The house is a treasure trove of day-to-day living in Oakwood from another time. You'll see common items, such as vintage furniture and toys, but you'll also discover rarely found items like tissue boxes unopened from the mid-1950s or all the photographs, boarding passes, and ship layout from the family's only vacation in 1938 to Greece, their homeland. The décor of the home is also untouched -- it looks like the owners just moved in and are out on an evening walk.

Harry Costas immigrated to America from Greece in 1914 at the age of 14. He followed an older brother, John Costas, to Rhode Island. The brother was working in Rhode Island and found a job for Harry as a cook in a private school. The agreement was that Harry would do the cooking, and the school would give him an education. After receiving his education, Harry decided to make his own way and came to Dayton. When Harry arrived in Dayton, he opened a restaurant at 131 S. Jefferson Street near the intersection with 4th Street. The restaurant was the cornerstone of this busy neighborhood for over 40 years.

In 1940, Harry and his young wife, Keraloula, known as Koula, decided to follow some of their friends and moved to Oakwood. It was a perfect place for immigrant parents to raise their children and provide them with a better life—a life that would allow them to follow the American Dream.

This house and the story of the Costas family reflect what was happening at a national level with Greek immigrants in America. Before 1890, there were very few Greeks in America. Greeks chose neighboring countries in the Balkans, Egypt, and Russia where Greek communities were established and thriving.

Then there was a great wave of Greek immigration to America. From 1890-1920, there were more than 400,000 mostly male immigrants from Greece (including the father in this house). There were more than 100,000 Greek immigrants with Turkish passports (mostly arriving 1900-1925). This amounts to three-fourths of all Greek males between ages 15 to 45 left Greece for America. There were two main reasons for immigration to America. They came to America for economic reasons hoping to earn money for their family back in Greece. At the beginning of the 20th century, America was experiencing a rapid industrialization and urbanization. There were jobs in the cities for these immigrants. There was also growing political turmoil with Turkey resulting in increased hostility for people in the Thrace region of Greece.

Greek immigrants primarily went to three places in America. If they went to the Western states, they worked on railroads and in mines. In New England, the Greek immigrants worked in mills and textile factories. And third, Greek immigrants flocked to Northern cities including Dayton. Here they were restaurant and factory workers. Like Harry Costas did. His story is typical. He comes to Dayton and settled with friends. And together they establish a Greek community.

As a group, there was a cultural yearning to return home to Greece. Because of this yearning the Greek population remained culturally isolated. They knew little to no English. They didn’t know American laws or customs. And they felt a loss for their own culture, holidays, and religion. The Greek Orthodox Church and the “Greek Towns” filled this void.

The Greek immigrant experience in Dayton is similar to the larger Greek experience across America. In 1900, there were five Greek families in Dayton with an average wage of $8 a week (same as $200 today). In 1910, there were 15 families, which was enough to hire a traveling Greek Orthodox priest to visit Dayton once a month. By 1921, there were 65 families in Dayton with more than 30 businesses including restaurants, confectioneries, bowling alleys, furriers, grocery stores and shoeshine parlors. The Greek businessmen catered to the growing urban populations on the busiest streets in downtown Dayton. As shopkeepers and business owners the Greek population moved into American middles class.

Yet they wanted to retain their Greek identity and values. Within the Greek community there was an emphasis to marry someone Greek. There was also an extended family structure that included the nuclear family, extended family, godparents and close friends. Through several hundred years of conquerors and enslavement, the Greek people came to rely heavily on the family unit and the church body.

In 1921, the 65 Greek families collected $5,000 (around $58,000 today—if divided evenly would be nearly $900 a family) toward the purchase of an existing church at 15 S Robert Boulevard along the river between Third and Fourth Sts. The church provided the spiritual and social needs of the Greek immigrants. The church was a place for Greek members to speak their native language and men to do business. There were clubs and Hellenistic orders for men, women, boys and girls. The Greek Orthodox Church maintained the ethnic and religious heritage of Greece. It celebrated the religious and national holidays.

By 1930, more than 100 Greek families lived in Dayton, and about 90 of these families lived in the area of West Fourth, Proctor, and Maple Streets within walking distance to the Annunciation Church on Robert Blvd. Greeks owned many small shops in the area bounded by Main, Ludlow, West Second and West Fifth Streets. Those proprietors and employees living in the neighborhood of the Church could easily walk to work.

Other Greek families in the 1920s and 1930s lived across the Miami River on West Second and Grimes Street, in the Five Oaks area of Dayton View, and on McDaniel Street and Floral Avenue in the Riverdale area. A few families lived in south Dayton and Oakwood.

In the late 1930’s people began to move from these neighborhoods to other parts of the city, and by WWII the Greek neighborhood around the Robert Blvd. church was gone. After WWII, the church members built the new church over on Belmonte Park North behind the Dayton Art Institute.

Harry Costas was born Aristides Constantinov in a rural border region of Turkey known as Thrace or European Turkey. Records show him using both his Greek name and Americanized versions including Aris Costas and Harry Costas. Harry came to America in September 1912. It is likely he left Turkey because of the upheaval in his hometown area and for all the reason’s explained outside.

When Harry left Turkey, he was just 14 years old. He was following in the footsteps of his older brother, who had left just a few years earlier. His brother had secured a job at a boarding school in Rhode Island. The East Greenwich Academy, a private Methodist school, had agreed to give the boys their education in exchange for them working as cooks. This was a good deal for Harry not only did he learn to read, write, and speak English; he also learned the profession that would allow him to become a successful businessman in Dayton.

Harry remained at the school until 1917 when he enlists in the Army as a cook. Then the US enters World War I. All resident aliens who had not been naturalized were required, as a security measure, to register with the U.S. Marshal nearest their place of residence. If he failed to register, Harry risked interment or possible deportation. This registration occurred between November 1917 and April 1918.

In addition to the Resident Alien registration – there was the new Selective Draft. The "Select Service Law" was an Act of Congress, which came into full force May 8, 1917. It was hoped and intended to raise our new army in a way that would leave as many agricultural workers as possible on the farms to keep the world from starving, and to take men, as much as possible, from the occupations which were less essential.

It was a double whammy for Harry. There was a cultural call for Allied Resident Aliens to fight along American citizens in Europe, and he was a cook qualifying under the Selective Draft. 1.2million aliens registered, 500K were called to service. Thousands of Greeks served in WWI. Harry was honorably discharged a year later.

After service, Harry made his way to Dayton, Ohio. In the years following WWI, the number of Greek immigrants was drastically reduced. The restrictive Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 made immigration quotas permanent. Countries most favored were Great Britain, Germany, and Ireland. Countries whose immigration had increased dramatically after 1890—including Italy, Poland, Russia, and Greece—had their quotas drastically slashed.

Harry remains a Resident Alien for over 10 years. He becomes naturalized in 1924 at the age of 27. It is not known why he did not naturalize earlier, but he did naturalize during an era of stricter immigration policies. These began during WWI as the US government began to put quotas on how many immigrants for any given country could be naturalized in a year. There was also a grassroots push to naturalize with Naturalization Bureau publishing its first Federal Textbook on citizenship in 1918. These booklets were distributed to public schools offering citizenship classes and notified eligible aliens of their education opportunities.

After his honorable discharge from the Army, Harry left Rhode Island to make his way to Dayton. As you heard outside, being a store/restaurant owner was a very popular first-generation Greek profession. And according to his son, the restaurant was his life. It allowed him to provide well for his family and increase his wealth to afford toys—like a car!

His son, Jim said, before Harry was married he was the activities director for Jefferson Street! He took his friends to ball games and movies in his Studebaker car. And why a Studebaker, because one of his customers at the restaurant was a mechanic and worked on Studebakers—Harry switched to Nash’s when the mechanic started working on them.

Harry also went to a friend’s house for dinner—John Apostolou and his wife, Kokonie. While at the dinner, Harry commented on how good the food was and how did Kokonie have any sisters—I need a wife. And sure enough, she did—a sister back in Greece named Kereakoula, Koula, for short.

Harry began writing to Koula and in 1930 after a short courtship over letters, Harry left for Greece on January 21, 1930. Harry (33) and Koula (18) were married on February 2 and the couple returned to Dayton a month later on March 6th. Just six weeks, and everything changed.

The couple returned on a ship known as Saturnia, it was part of an Italian line of passenger and cargo ships. The ship traveled from Trieste, Italy, to New York City. The average transatlantic trip took 4 to 5 days on boat, not to mention the land travel to get to ports. Therefore, a trip to “the old country” was very important. And as we can see in the photo of Koula and Harry on their voyage home—the two look like strangers but Koula has an air of excitement about her.

Little is known about Harry and Koula’s relationship. Their son Jim described his father as outgoing and always working. His mother was a homebody, she wanted isolation. She stayed up late watching Johnny Carson and learned English that way—life in the household was stereotypical male and female roles. Koula did the cleaning and cooking, she did not participate in church activities but church was extremely important to her. She managed the household. The couple never went to dinner together, they never entertained, and the family went on one vacation to Cedar Point and after two days— according to Jim—Harry was itching to get back!. It is therefore not surprising Koula saved so many things from her 1938 trip back to Greece.

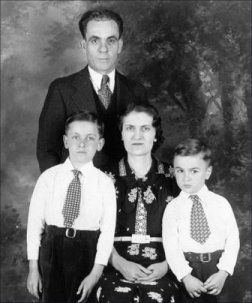

One of the memories that Koula appears to have held close to her was the 1938 voyage back to Greece to introduce her family to her boys. After Koula becomes naturalized in 1937, it was safe for her to return home with her two boys— Konstantine, known as Connie, born in February 1931, just 11 months after the wedding and Demeipios, known as Jim, born only 19 months after Connie.

Harry and Koula likely saved for several years for this trip and it was also likely that Koula returned to Greece while both boys were under 10 years—since after 10, children were charged the same fare as an adult. Therefore, in April 1938 when Connie was 7 and Jim was 5, Koula took them alone to visit her family in Greece. The three left from New York in April on board the Saturnia, the same Italian Line Tourist Ship that brought Koula to America after she married Harry in 1930.

Koula saved the advertising brochures from the ship—which explains the route and cost. Jim remembers the trip and the stops in Tunisia where he rode camels. From these brochures we can see that April was considered the low season for travel to Europe, however, the ship advertises that its southern route provides mild temperatures so its passengers can enjoy the deck all year around. The ship offered salons, music rooms, verandas, bars and smoking rooms, sunny game and shaded promenade decks, and swimming pools. The decks had several sports that could be played and evening dances, movies, and strolls under glittering stars. These offerings were to keep passengers entertained on the voyage that took nearly 5 days.

The cost for this trip was $162.00 dollars one-way for Koula ($2,600 in today’s money), another $162 for both boys since they were charged only half the full fare. This is a total of $324.00 ($5200.00 today’s money) for the trip TO Greece on boat alone—this does not count the cost for land travel or day-to-day expenses occurred while traveling or the trip back home! What is amazing about this number—is that the average American family in 1938 had $492 of spending money per year. Therefore, a trip to Greece was basically, all the family’s spending money for a year. This does not take into consideration the monetary gifts the family likely brought to their relatives.

It might sound surprising but while interviewing Jim last month, we learned that Harry sent a letter to Koula to cut the trip short and come home early because he was worried about Hitler. The first document that indicates Koula and the boys are back in the United States is the July 1939 purchase of the house. Jim’s memory is that they were back before 1940. This gives you some idea of how long a family might stay after such an important and expensive trip.

But Harry was right to cut the trip short and it is likely that Koula and the boys returned in early 1939 or late 1938. Since in 1938 when Koula and the boys left Hitler was making threats to Czechoslovakia and Poland as well as persecuting Jewish citizens in German. Koula’s passport notes that there is unrest in foreign countries and it also indicates that she and the boys are not to travel in Spain. However, no nations had officially declared war on each other. But that did not take long, in September 1939, Hitler invades Poland and nations around the world start to take sides and declaring war on one another. The invasion of Poland is commonly referenced as the beginning of WWII. In 1940, Italy becomes an official Axis power—Italy—the country of their ship back home. So it was good that Harry called his family home when he did. In October 1940 Italian troops invade Greece and are met with strong resistance. This is the beginning of Hitler’s Balkan campaign.

This is the room of the two boys in the family, Jim and Constantine (or Connie). What would their life look like as two young boys in Oakwood in the 1940s and 1950s?

First, the Greek family was very important. Koula, the mom, had a sister in Dayton. She would visit, often being driven by the neighbor James Thomas (a Greek man on Wiltshire and owner of a hat shop downtown). The sisters would have parties and afternoon tea while the cousins would play.

Jim and Connie would walk each day with friends to Edwin D. Smith School and then the junior high and high school. Most kids walked home for lunch each day, as they did. Most families had just one car and the father drove to work, and the mother stayed home.

There were 10 or 12 kids on the 400 block of Wiltshire and the immediate surroundings in the 1940s and 1950s. The kids played in the grass right of way (or alley) behind the houses and in the vacant lots. The trees were new and short. The kids could punt a football or hit a pop fly easily in the street or the vacant lot on the block. Jim and Connie would wait on the kids to come out from dinner to play ball. Later in the evening, Harry, the father, would come home from the restaurant and the kids would eat dinner after it was dark. On some nights and summer days, the kids would play football at the Smith School yard. The Oakwood kids organized themselves into neighborhood teams. Jim and Connie were on a team that included Hadley and Wiltshire kids. Their team was known as a good team with tough kids. There was the occasional fight. Jim recalls the Walling family’s 8 kids across the street where the police would just show up and ask questions whenever something mischievous happened around town.

The kids would ride their bikes to the Far Hills Theatre (near today’s Talbot’s store). Jim recalls 100 bikes in the small parking lot on Saturdays. On other days, the boys would ride their bikes to Brownies grocery store in the 300 block of Hadley (314 Hadley). They’d buy a coke, sit on his steps, and then return the empty bottle. Jim recalls a welcoming and trusting owner where kids came and went, helping themselves as they pleased. He also remembers a .38 revolver under the counter. The boys also frequented Gallagher’s Drugstore, Gunther’s barbershop, and the Far Hills Pharmacy. They would buy fireworks from the DLM fruit stand on the Fourth of July.

The boys didn’t work in the restaurant with their father, but they did carry money to the bank for him. The father would also bring home the pennies and the family would sit and roll them together.

This childhood experience is similar to many boys around Oakwood at this time. What would be different than other boys was their Greek heritage and the role the Greek Church played in their life. For several years, Jim and Connie would travel downtown after school a few days a week for Greek School. Greek School would teach the Greek language and Greek history and culture. Jim recalls in sixth grade taking the bus downtown. He walked into the Elder-Beerman store and rode the new escalators for an hour skipping Greek School. He walked to his dad’s restaurant on S. Jefferson St. to get a hamburger and a piece of pie. Then he’d take the bus back to Oakwood. After several weeks the teacher and Koula figured out Jim’s plan, and it was stopped.

When we met with Jim, there were so many nice stories about growing up in Oakwood—but one of the most endearing ones about getting groceries. Koula was an introvert—she was never comfortable with her English language skills, but she did not even socialize with the other Greek women in the neighborhood.

So, we asked Jim where did she grocery shop—and his reply—“Oh that is a good one.” His mother did not go grocery shopping. Instead, the meat came home with Harry from the restaurant and all the other goods—well, Jim and Connie took their bikes with baskets attached to Drummond & Sloan (today’s Talbots’ complex). Koula would write out a list, give the boys exact change and send them on their way. Jim said there was room enough for two shopping bags.

Jim also remembers one other household duty his mother passed along to the children and that was—purchasing her Turkish coffee. The stores up here in Oakwood—did not carry specific ethnic specialties ... so Jim had to go back to the old neighborhood where a store would sell Turkish coffee. This was more difficult than it sounds—for as a 7- to 8-year-old, Jim would catch the streetcar on Far Hills ride it downtown, transfer to a trolley that stopped at the store—and then come back the same way. Jim remembers not likely this job since it cut into his time playing football with the neighborhood boys for it took nearly half the day.

The family continued to enjoy this home until 2011 when Connie died. Harry was the first to pass in 1968. He continued running his successful restaurant, The Delmonte, on S. Jefferson Street, and as his son Jim said—was the mayor of Jefferson Street for many years. Harry was proud of his college-educated boys—Connie was a successful businessman with NCR and Jim was a dentist in Centerville, Ohio. Connie returned home just before his father passed—to help with the house and never left. He and his mother lived together until her passing in 1994 and then Connie lived here alone.

The construction of the house cost the Freuds $7,100 in 1929. This is approximately $100,000 today. The Freud’s were older when they built this home and never had children. They lived in the home for only three years before selling to another older couple without children—J. Clifford Hull and his wife Katharine. These two appear to be retired for the six years they live at 413 Wiltshire. Then in 1939, Harry, his wife Koula, and their two boys decide to move into Oakwood after Harry’s Greek friends persuade them to come.

The Costas’s took a mortgage of $4,000 for the house approximately $67,000 in today’s money. This figure of $4,000 was the national average for a house. And it is reflective of the national average for a yearly wage, which was $1,730 or $28,000 in today’s money.

This house—like homes throughout Oakwood represent the national shift away from elaborate Victorian architecture like Queen Anne, Second Empire, and Richardsonian Romanesque to a more simplified expression most commonly found on the two most popular building types—bungalows and foursquares.

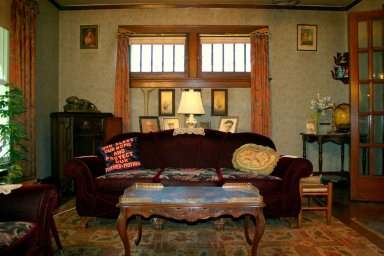

The Arts and Crafts bungalow is extremely common in the 1910s and 1920s. Its architectural characteristics include the overhanging eaves, a full-width porch with massive columns, and simple details that do not clutter the building—things like 4/1 double-hung sash windows with the panes divided with vertical mullions. But the interior of this home represents the liberal use of mixing old with new. The furnishings are both Craftsman and Colonial Revival. The bones of the house include the lovely mantel, folding French doors, and built in including benches and window seats. The decorations represent 70 years of a single family living here. We are lucky to have so many of the family’s original pieces including furniture, rugs, wallpaper, lights, pottery and never painted woodwork. To find a house that was pure in its architecture and decoration was very uncommon. Instead, you had consumers with many choices. . There were so many magazines from this time that were advising housewives on what to purchase and how to decorate.

— well, the 1880s and 1890s America saw a shift from an agrarian-based economy to an urban industrial one. As this shift was occurring, it created a rising wealthy class and a lot of unskilled labors (both immigrant and “off the farm”). However, soon the labor was becoming more skilled and there was more need for managerial level jobs, and quickly there is a second shift to a strong, dominant middle class.

And quickly, all consumer products were geared towards the middle class and their wants and needs. As the change occurred in the 1910s and 1920s there is this shift in architecture and decorative arts away from the fussy houses with separate rooms for separate functions and towards a house that was simple and could be decorated and maintained by a single person, the housewife.

Unlike earlier generations where immigrant workers were looking for low paying job as household help or the jobs of a farm family were just too big for one person so daughters and relatives were brought into the house to help the housewife —as the 1920s came around—technology and simple homes like the bungalow allowed writers of the time to promote the housewife to doing all the cleaning, cooking, and buying for the home.

Well let’s look at the spaces—there are four rooms on the first floor. Within these four rooms all the public life of the house took place. The spaces therefore had to be uncluttered. So, we see things like built-ins, we have lamps hardwired into the mantel and newel post along with overhead lighting to provide light without taking up unnecessary floor space.

We also see the age of a modern home. No longer are bathrooms retrofitted as indoor plumbing becomes readily available instead bathrooms are modern, clean, and built with the home. When you go upstairs, take time to look at the bathroom. It is not until after WWI that bathrooms become standard in building. The bathroom here is so like the advertisements by American Standard and other plumbing manufactures of the time.

Other things you don’t see that make this home modern are the gas fireplaces—wood was old-fashioned and messy. There is also forced air heating. The kitchen features linoleum and while the product was available in the 1880s the inlay technique that allowed for decorative patterns was a newer option. You will see things like rugs and curtains. All of these are store bought—this is a time when middle-class consumers had buying power and they could decorative their home in a manner that was not available just 20 years earlier when everything was made at home or the cost for store bought was so high that only the wealthy could afford. The placement of the furniture throughout the house is how Jim, the son, remembers it all his life. His mother wanted to protect her nice, store bought things and sewed covered for the couches and chairs, kept the cushions flipped over so no one sat on the good side. She never served dinner on the dinning room table— instead the family ate all meals, even holidays at the kitchen nook.

Cleaning was another big part of a housewife's job. While upstairs notice that all the furniture is off the walls. This allowed for easier cleaning. Housewives of the time took great pride in their homes. The popular magazines were always advertising how new products will make your work easier.

However most of the duties of the house fell on Koula and when we think of the industrial revolution—we think of railroads and factories—but one of the most industrialized area—was the home. There is also the perception that machines made work easier—but in the case of the middle-class housewife this is not so. In fact studies from the time period show that the workload of a 1940s middle-class housewife actually increased from the generation before.

How can this be true? There are three parts to this puzzle—1. Due to immigration policies, domestic servants had declined. 2. The number of commercial services provided to the households also had declined. No longer were groceries delivered, the doctor came calling, and steam laundry had almost died with the advent of the washing machine and the seamstress had been replaced by ready-made clothes that you had to go and buy. All of this “running around” increased her workload and 3. The standards for housework had risen. People began changing two sheets a week instead of just one. Men stopped wearing detachable collars and cuffs , so the whole shirt had to be laundered. The new germ theories convinced people that bathrooms and kitchens had to be kept scrupulously clean in order to prevent disease and more and more information about nutrition meant meals had to be balanced. Also, most woman began to spend more and more time educating and entertaining their children. Becoming involved in school activities and taking kids to playgrounds and piano lessons.

It is during the 1940s that the classic American standard of living was taking shape—three square meals a day, scrupulous cleanliness of persons and places, compulsive attention to preventive medicine, concern with every child’s psychological and physical development. But at every step, there was more work for the middle-class housewives to do in their homes.